In the Georgian Criminal Justice System, the people are represented by two separate, yet equally important groups: the thief-takers, who catch criminals in the act (and sometimes work with them for a reward), and the Magistrates, who are usually heavily corrupt and often take bribes from the accused and the accusers.

These are their stories.

All silliness aside, in many respects, life in 18th century Britain would be recognisable to us today. They had coffee shops and seaside resorts, they read newspapers, they traded on the stock market, and they had a legal system based on evidence and trial bu jury. But in many other respects, it was wild and chaotic, and you wonder how anyone could accept living like they did. Of course, they didn’t–that’s why the system evolved into what we have today.

Back then, the list of things you could be arrested for was long and confusing, the methods of catching a criminal were hazy and mostly reliant on luck, and the court system was notoriously corrupt.

What is considered a crime?

The list of offenses that could be considered crimes was extensive, ranging from being seen on the King’s highway with a sooty face, to stealing from your employer, to murder. It’s difficult to find one definitive list because the law changed so much by region and over time, but we can see certain trends.

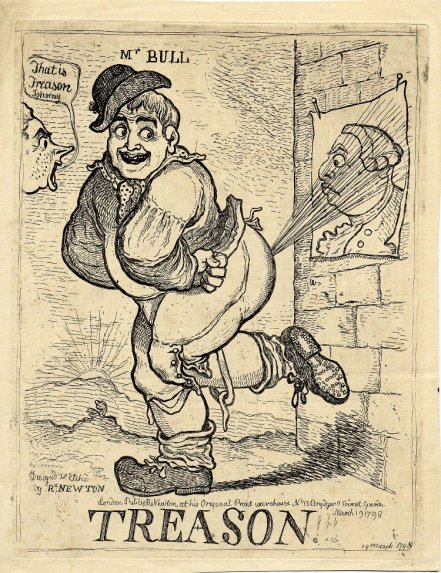

Obviously, crime against the State was a big one. Lots of things constituted treason, including farting on a poster of the king. Also, selling secrets to the enemy, piracy, defacing currency, sabotaging the military or public institutions, all that sort of thing was very serious and carried the death penalty. Sometimes protesting was considered treason, but it depended how, where, and when (the Licensing Acts of 1662 and 1737 made the satire we associate with the period possible).

No kidding

Next were crimes against the person. So, murder, manslaughter, assault, impersonations (especially of the clergy), and that sort of thing. Following these were crimes against property: theft, vandalism, damage to property, arson, stealing sheep and handkerchiefs specifically, and a card of white lace stolen by Jan Austen’s aunt from a milliner’s shop in Bath.

Jane Leigh-Perrot (Jane Austen’s aunt) was totally a thief

People’s sex lives were of particular interest to lawmakers of the day. Bigamy, sodomy (homosexuality), buggery (bestiality), masturbation, and pretty much any form of sexual behaviour not specifically endorsed by the Bible were strictly off-limits. Punishment in these areas could be more lenient, however, depending on a number of circumstances. For instance, there’s a case from Wiliamsburg where two young men avoided the death penalty because their behaviour only ‘tended toward sodomy’ and therefore no crime was actually committed, and the man who reported the incident was made to watch as he was believed to be ‘not without fault himself’.

Then came various and strange grievances like associating with gypsies, swearing, chipping stone from Westminster Bridge, and enjoying oneself during the hours allotted to worship.

How was crime detected?

In London

The actual detection of a crime is a mostly Victorian concept, when the birth of the detective policeman was invented. Before that, it was the responsibility of the victim to haul the accused before the magistrate, which almost always meant facing them in court. In London, there was an organisation called the Bow Street Runners, the very first proto-police in the country. They could catch criminals (usually in the act), or else run them to ground. The sort of Sherlock Holmes/CSI thing we’re used to, the world of forensics, crime scenes, and clues were wholly alien concepts to people in the 18th century.

Magistrate Sir Henry Fielding, who founded the Bow Street Runners

Elsewhere

Outside of London, things get a bit hazier. The victim still took their perpetrator to court most of the time, but there was also the class of people known as thief-takers. These were a lot closer to bounty hunters than police. And oftentimes, they were in league with the criminals themselves. They would take their cut of any spoils, receive payment from the aggrieved to track down the perpetrators, then be paid by the magistrate if the trial resulted in conviction, and occasionally even more if it ended in an execution. Not all thief-takers were like that, of course, but enough were that it became a common assumption that law enforcement was no better than the criminals.

In fact, the criminal justice system was so unabashedly corrupt that people, like today, sympathised more with the criminals. Pirates and highwaymen were just as popular back then as they are now (though, legitimately also highly feared). Many of them were quite famous and protected by the people, and there are still surviving songs and stories about the most audacious of them.

Dick Turpin is probably the most famous example.

Dick Turpin on Black Bess

Because crime was so difficult to detect unless criminals were caught in the act, the punishments were intentionally harsh, to deter people from committing them at all. In the 1790’s, there were 200 offences that carried the death penalty.

So you’ve been arrested. What next?

So you’ve been charged with a crime. You’ll be taken before a magistrate or a judge. Usually trials went quickly, sometimes taking as little as 15 minutes start to finish. You are not allowed to see the evidence presented against you beforehand, but you are allowed to write a statement in your defence and you are allowed to call witnesses to speak on your behalf. If you are wealthy, eloquent, well-mannered, well-connected, and well-educated (like Jane Austen’s aunt), you have a good chance of getting off. But I’m giving you a bad day, so you’re not. You are convicted.

Oh yeah, and witness intimidation is totally allowed.

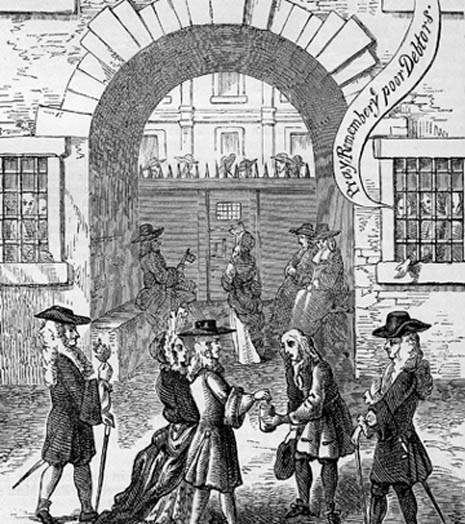

So now, you get sentenced. Based on the severity of your crime, your behaviour in court, your social standing, race, sex, religion, possibly political leanings, and whether or not you’re a foreigner, the judge will decide what is best to do with you. You could be fined heavily (just enough so that you can’t afford it, at which point all of your possessions will be sold and you and your family will have to go to the debtor’s prison), you could be branded, you could be whipped, imprisonment (though, imprisonment as a punishment in itself wasn’t widely used), and being forced into military service (many chose ‘the King’s shilling’ over other forms of punishment).

He’s in a bad mood, so you’re going to be sent to the colonies. It’s the 1790’s so probably Australia. You’ll be held in a prison until a ship is ready for you (and you’ll have to pay jailor’s fees. If you can’t, your wife and children will go to the debtor’s prison until you complete your sentence, return, and make enough money to bail them out). If you’re lucky, you’ll survive the hard labour and harder inmates, and return to England in a few years, where you’ll spend the rest of your natural life trying to repair your reputation and earn a living.

Pray, remember ye poor debtors!

Or not.

Relevance to my story

My two main characters, Alois and Sulat, support themselves through crime–theft, mostly. They operate in a world where there exists a sort of magic black market, and they are employed by various people to find, retrieve, and deliver valuable magical items. Quite apart from the danger inherent in this line of work, the threat of detection and arrest are never far off. They use a variety of techniques (mostly running and hiding) to avoid being caught, but it doesn’t work every time. The thief-takers, Huw and Col, know their style, and lie in wait to catch them.

Andra is a smuggler who often hires Alois and Sulat to find things for her clients. She doesn’t like to get her hands dirty, and she finds the handing out of contracts and the delivering of goods to be more her speed.

Roul and Timur work as Andra’s enforcers. They’re huge, brutish, and not too bright. They are not known to carry weapons, as their size and strength is usually enough to deter too much backtalk. Andra keeps them in line through a combination of cunning and bribery. Usually, that’s enough…

Spotlight on Huw and Col, thieftakers

Huw and Col don’t get a whole lot of time to explain themselves in Magic Beans. There may come a day in later books when I delve deeper into their lives, but for right now, they serve mostly as the ever-present spectre of Justice that hound out heroes. So I’ll go a little into their back story here.

Huw and Col were childhood friends. Huw was a hunter and Col was a musician before the Ettin War. When the fighting started, they both signed up and did their bit. However, while the able-bodied men were fighting, the less altruistic members of society ran rampant with no one to police them.

During a particularly nasty battle, Col’s hand was smashed and he lost the fine motor skills he once prized. Since then, he has regained most of his functions, but he can never play like he used to. He lost his way, and turned to petty theft. Huw returned from the fighting to find that an elderly woodsman friend had been attacked and killed. Huw, always more serious and intense than Col, turned his skill at tracking and fighting and his newfound rage to thieftaking.

Their paths eventually crossed when Huw was hired to capture an auburn-haired dandy and chased his old friend to ground. Unable to take Col before the magistrate, for he would surely hang, Huw decided to forfeit his fees and harbour Col if Col agreed to give up thieving and join him in the business. Col agreed, and they’ve been working together ever since.

Col, the charismatic and charming one, usually deals with the clients, and Huw, the experienced and level-headed one, does most of the actual work.

Whatever the thing is, seriously, don’t do it.